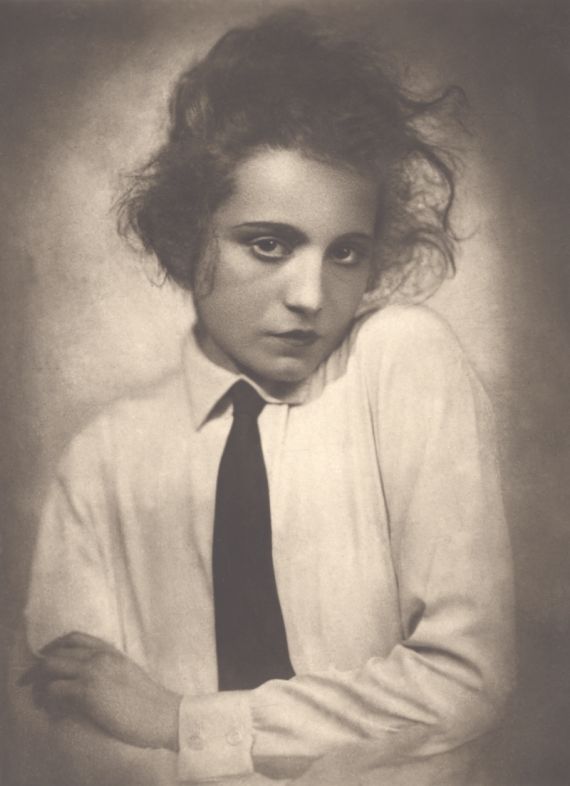

Porträt von Speedy Schlichter, 1929

© Deutsche Kinemathek – Hans G. Casparius

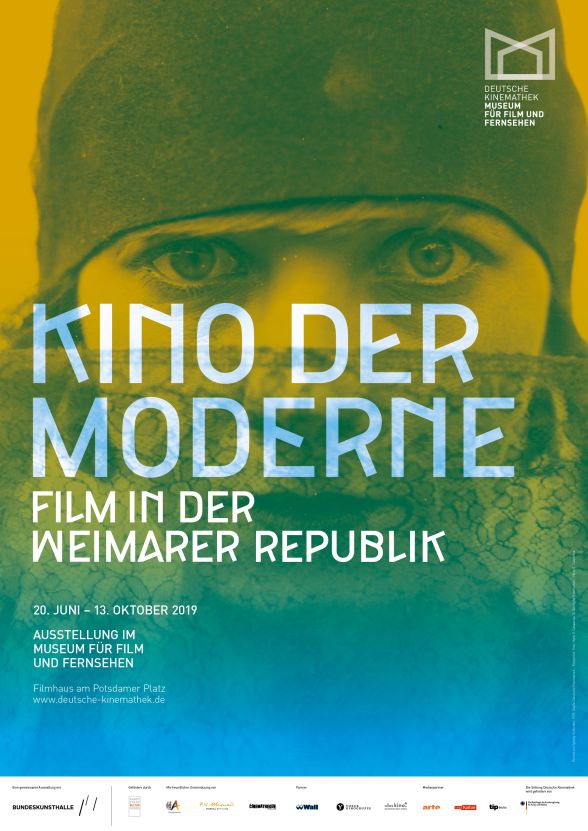

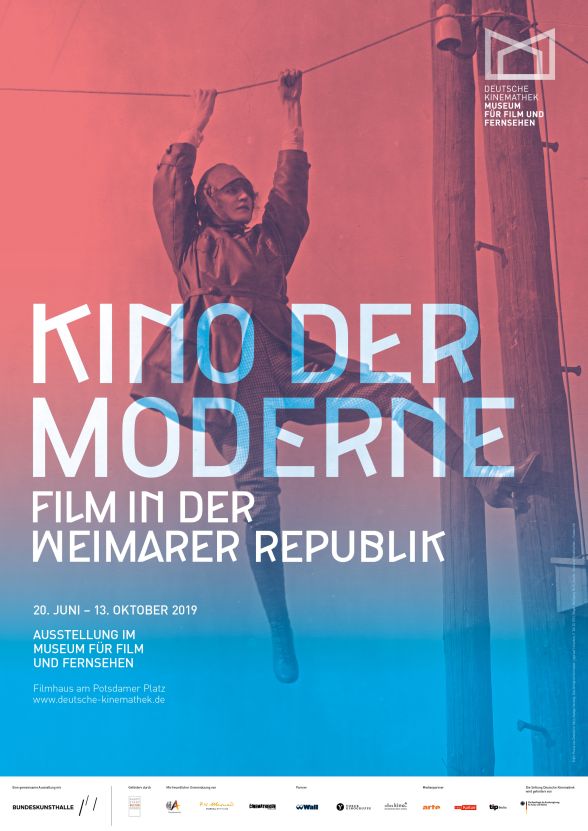

Modern Cinema – Film in the Weimar Republic

20.6. – 13.10.19

100 years of Weimar, 100 years of modern cinema – we look back at the relationship between cinema and everyday culture, the innovations of the film trade and the emergence of film criticism and theory in the 1920s.

Like no other art form, cinema reflected the spirit of the modern era: fashion and sports, mobility and urban life, gender issues and the emergence of psychoanalysis characterize the films of the period, which would have a profound influence on international film aesthetics.

Screenplays, posters, props and cameras highlight film’s references to literature, arts, architecture and social developments. The exhibition also sheds light on the work of women behind the camera. It presents 21 women professionals within the film industry who played decisive roles as producers, directors, screenwriters, or set designers.

Along 23 main topics, we lead you through the "roaring 20s" – from the first cinema palaces right into the heart of Babylon Berlin and to the sudden end of artistic freedom under the National Socialists.

Trailer

Enjoy a small foretaste of our exhibition and race through the lifestyle of the 1920s in 30 seconds.

Music by Richard Siedhoff.

Main Topics

-

View and download chronicle as PDF

Chronicle 1918–1933

All political, cultural and cinematographic events in the Weimar Republic at a glance.

Weimar, Feminine

Elisabeth Bergner, 1922

Photo: Angelo Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive

After the First World War, many women take advantage of the opportunities now available within the emerging film industry. They strive to establish themselves primarily as screenwriters, directors, or producers. In the credits, they usually do not mention their first names. A conspicuous number of them have double surnames–this, too, is an expression of a new era.

One gallery presents roughly twenty female film professionals with biographies and exhibits. Film excerpts document their diverse work; an audio station also lets the women speak for themselves on the basis of autobiographical texts and report on their experiences in the film business. A largely unknown chapter of Weimar cinema is thus given both a face and a voice.

Stars and Fans

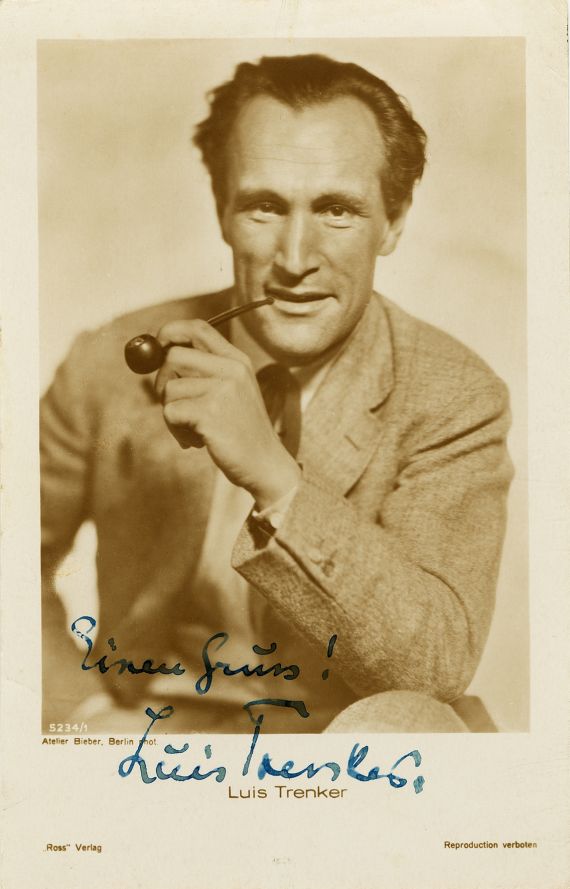

Star postcard of Luis Trenker

Photo: Atelier Bieber, Berlin

Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive

In Germany, a star system modelled after Hollywood–and with this a corresponding fan culture–establishes itself quite early. Postcards with portraits of the stars, home stories, and autograph sessions are examples of the staging and marketing of film celebrities such as Brigitte Helm, Henny Porten and Emil Jannings. They function as role models and are also in demand as brand ambassadors.

As role models, they offer a variety of opportunities for identification: Elisabeth Bergner is seen as being dispassionate, Leni Riefenstahl as athletic, and Lil Dagover as ladylike. The spectrum of young lovers ranges from the melancholic Conrad Veidt and the worldly Franz Lederer to the carefree Gustav Fröhlich.

Visual artists are also inspired by the charisma of film actors: Hannah Höch collects press photos of Anna May Wong and Marlene Dietrich, while Herbert Bayer collages images of Louise Brooks.

Urbanity

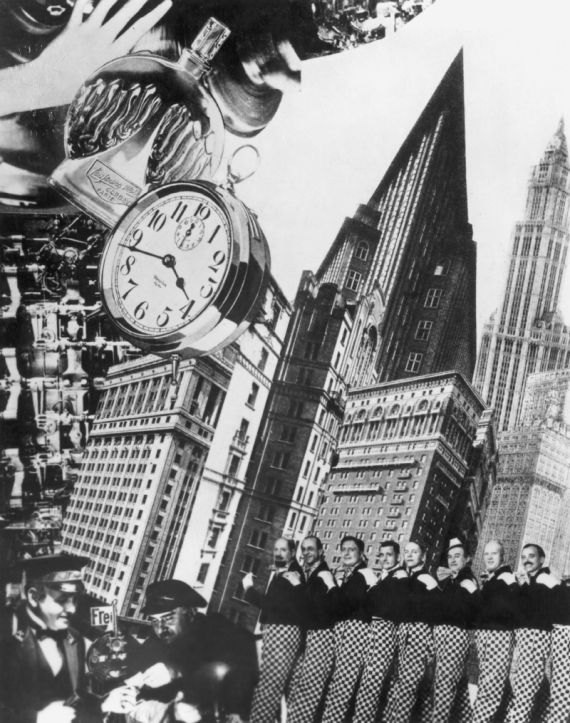

Collage, presumably by Umbo

Berlin. Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt (Berlin. Symphony of a Great City, 1927, dir: Walther Ruttmann)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive

The metropolis becomes a visual symbol of modernity. The nervous rhythm of life and the juxtaposition of different social realities culminate in this metaphor. Against the backdrop of the metropolis, numerous contemporary themes are played out, be they love stories, comedies, or dramas. The movements of the protagonists–from the flaneur to the criminal–determine the pace of narration and the cinematic perspective.

The vision of the vertical city with its spectacular skyscrapers is portrayed by Fritz Lang in Metropolis (1927). The photocollages created by the artist Umbo and the director Walther Ruttmann to promote the experimental documentary film Berlin. Die Sinfonie der Großstadt (Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, 1927) celebrate the myth of a city that never sleeps.

Social Issues

Company photo

Käthe Kollwitz on the set of Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Glück (Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness, 1929, dir: Phil Jutzi)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive

During the Weimar Republic, an increased rural exodus set in, for cities promise the prospect of work. The consequence is a drastic housing shortage, especially in fast-growing Berlin. Social disparities rapidly escalate and are addressed in both feature and documentary films.

The artist Heinrich Zille collaborates with the director Gerhard Lamprecht in a production that focuses on social ills within the working-class milieu. Together with other artists, Käthe Kollwitz supports the leftist film project Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Glück (Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness, 1929).

Ella Bergmann-Michel documents soup kitchens for the homeless in Frankfurt am Main and, with her film Wo wohnen alte Leute? (Where Old People Live, 1932), points to an alternative in social housing.

Avant-garde

Lotte Reiniger at work on a silhouette film

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive

At a very early stage, cinematography is already influenced by the artistic avant-garde, and Expressionist film sets a first milestone. The set designs by Hermann Warm and Walter Reimann for Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, 1920) reveal new perspectives for deliberately non-realistic cinematic art.

Visual artists such as John Heartfield and George Grosz are involved in feature film projects. Oskar Fischinger’s abstract image-sound compositions attract the interest of the advertising industry and later of Walt Disney. With her silhouette films, Lotte Reiniger creates a new form of animated film.

Experimental filmmakers such as László Moholy-Nagy, Hans Richter, and Walther Ruttmann also engage with the new medium on a theoretical level, and writers such as Bertolt Brecht and Arthur Schnitzler try their hand as screenwriters.

Gender

Travesty scene with Curt Bois (as Egon Fürst) and Mona Maris (as Princess Antoinette)

Der Fürst von Pappenheim (The Masked Mannequin, 1927, dir: Richard Eichberg)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive

The “New Woman” is the key buzzword with regard to gender relations in the 1920s. The self-confident woman who takes her life into her own hands becomes a role model for a younger generation. Fashionable accessories such as neckties and top hats are no longer the sole preserve of men. So-called “trouser roles” allow a playful game of gender swapping, and homosexuality is also taken up by film.

The feature film directed against Paragraph 175 of the German Criminal Code, Anders als die Anderen (Different from the Others, 1919), was written in a brief censorship-free phase with the support of the sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld. Especially women filmmakers draw attention to the debate over the abolition of the abortion law (Paragraph 218). Mädchen in Uniform (Girls in Uniform, 1931) becomes a cult film within the lesbian scene.

Sports

Poster for Liebe im Ring (Love in the Ring, Reinhold Schünzel, 1930)

Design by Josef Fenneker, 1930

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Josef Fenneker Collection

© The City of Bocholt (Stadtmuseum Bocholt / Josef Fenneker)

In the 1920s, sports become a mass phenomenon. Due to shorter working hours, the work force has significantly more leisure time. Sports activities, especially soccer, boxing, and mountain climbing, as well as cycling and motor sports, are popular leisure activities and find their way into film.

World boxing champion Max Schmeling conquers the silver screen with Liebe im Ring (Love in the Ring, 1930). His fans come from all walks of life. Working-class sports experience a surge of popularity during this era. In the meantime, the well-to-do install private gyms at home, which is repeatedly satirized in comedies.

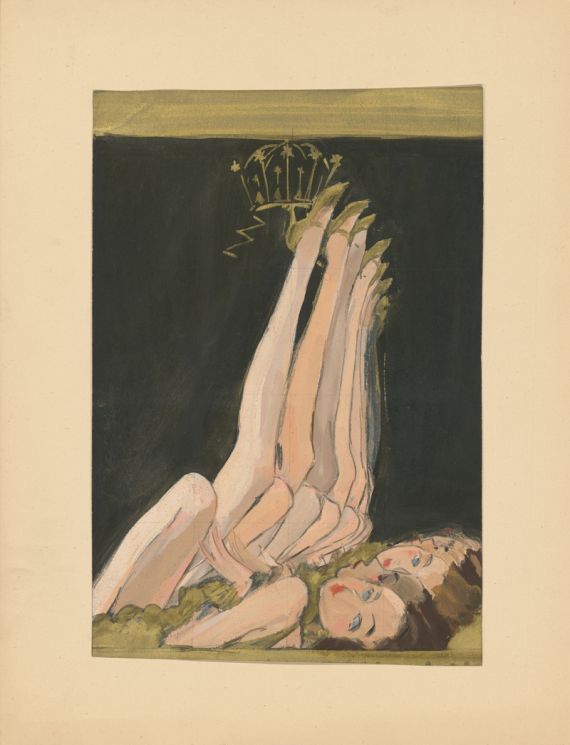

In Wege zu Kraft und Schönheit (Ways to Strength and Beauty, 1925), rhythmic gymnastics celebrates the ornament of the masses.

Fashion

Design for two women’s dresses by Aenne Willkomm, 1920s

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Aenne Willkomm Archive

The interdependencies between fashion and film are manifold: Aenne Willkomm, who designs the futuristic costumes for Metropolis (1927), also sketches knee-length skirts and dresses in tune with the times for various fashion studios. New fabrics such as rayon and charmeuse make sophisticated dresses affordable for “shop girls.” The female silhouette becomes increasingly slimmer and more boyish, and this ideal is also propagated in film.

Detailed articles in numerous journals are dedicated to film costumes and the wardrobe of the stars. Weekly newsreels report on fashion shows and beauty contests. Such a show is staged in detail in Der Fürst von Pappenheim (The Masked Mannequin, 1927). Fashion designers provide apparel for films and are listed by name for the first time in the opening credits.

Pleasure and Vice

Collage, presumably by Umbo

Berlin. Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt (Berlin. Symphony of a Great City, Walther Ruttmann, 1927)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive

“Licentious” Berlin presents itself in film in many facets. As an aspiring cosmopolitan city with tremendous social tensions, the metropolis is considered the nation’s hotbed of sin. Illustrated magazines, radio, and films present their audiences the rhythm of the big city: high-rises, neon signs, night clubs, travesty, jazz–and “girls.”

Alcohol abuse and prostitution are the downside of pleasure in films such as Tagebuch einer Verlorenen (Diary of a Lost Girl, 1929). Nevertheless, what is considered today the myth of the “Golden Twenties” was more likely merely a minority phenomenon.

Sciences

Photocopy of the hand of Fritz Lang, 1931

Marianne Raschig: Hand und Persönlichkeit. Einführung in das System der Handlehre (Hamburg 1931)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Marlene Dietrich Collection Berlin

Developments in science and medicine have a significant influence on the domain of cultural and educational film. The microscope and the telescope provide new views of the world. For the first time, the X-ray machine allows glimpses into the human body, and a camera mounted on the ceiling enables smooth shots of surgical operations.

George Grosz and John Heartfield illustrate Die Grundlagen der Einsteinschen Relativitätstheorie (The Basics of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, 1922) in the form of an animated film. In contrast, Die Biene Maja und ihre Abenteuer (The Adventures of Maya the Bee, 1925) is filmed with real insects with at times subjective camera settings from the perspective of the bees. The latest innovations in the field of criminology are taken up by film, as exemplified by Fritz Lang’s M (1931).

Psychoanalysis

Poster for Nerven (Nerves, 1919, dir: Robert Reinert)

Design by Josef Fenneker, 1919

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Josef Fenneker Collection

© City of Bocholt (Stadtmuseum Bocholt / Josef Fenneker)

The First World War brought forth a new illness, namely war neurosis. Already during the war, Sigmund Freud’s colleague Ernst Simmel developed a short-term therapy consisting of analysis interviews, hypnosis, and liberating role playing. Several films address the topic of psychological war traumatization, such as Nerven (Nerves, 1919), Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, 1920), and Zuflucht (Refuge, 1928).

Filmmakers and analysts alike realize that film is particularly suitable for depicting mental states. Sigmund Freud is invited to participate in various film projects, and two of his closest colleagues participate in G. W. Pabst’s Geheimnisse einer Seele (Secrets of a Soul, 1926). The depiction of dreams in the form of multiple exposures and crossfading continue to shape the aesthetics of film to this day.

Politics and Censorship

Friedrich Ebert with Henny Porten and Emil Jannings on the set of

Anna Boleyn (Anne Boleyn, 1920, Ernst Lubitsch), September 30, 1920

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive

The film industry follows the rise and fall of the first parliamentary democracy in Germany, bearing witness to its development from the November Revolution through the subsequent years of stabilization to the downfall of the republic. Its historical identity also becomes an important topic for cinema, whereby in all history films contemporary political conflicts play a powerful role.

After a brief censorship-free phase, a binding regulation on censorship was passed in 1920 with the first Reich Cinema Act. The Film Review Office in Berlin imposed mostly conditions pertaining to editing, as in the case of the revolutionary drama Bronenosets Potyomkin (Battleship Potemkin, 1925). In addition, screening bans, such as that imposed on All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) are the source of fierce controversy.

Nature

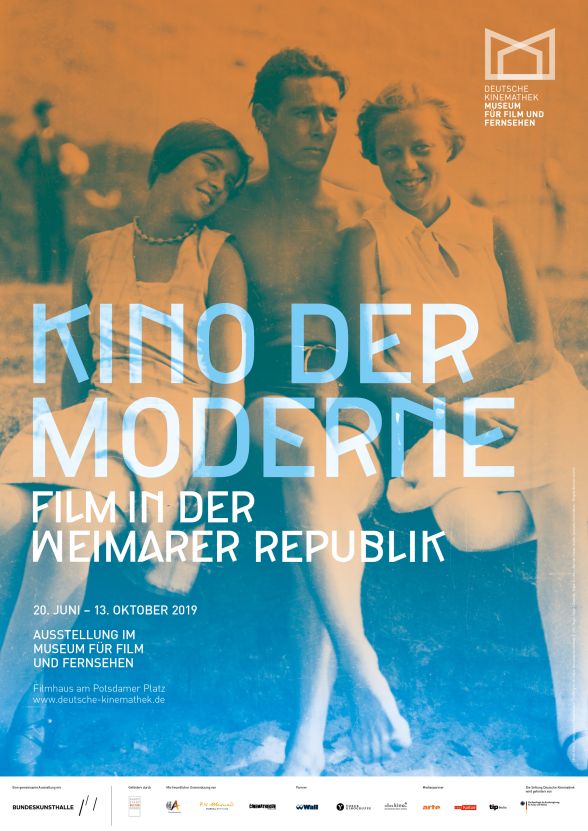

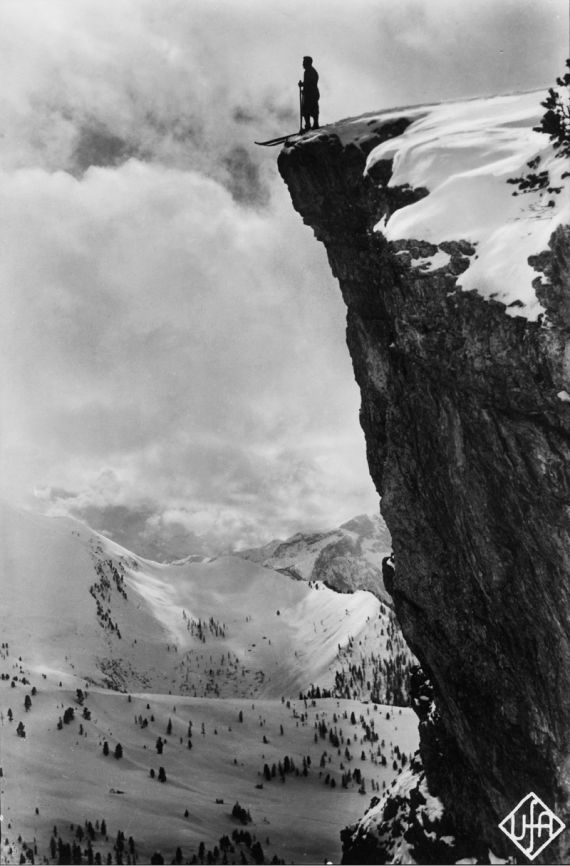

Scene from Der Heilige Berg (GER, 1926, directed by Arnold Fanck)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive

© Deutsche Kinemathek – Hans G. Casparius

After the hardships of the First World War, “summer retreats” become accessible for both white and blue-collar employees. Popular places of recreation and retreat from the city are rural areas and the sea. Menschen am Sonntag (People on Sunday, 1930), for example, follows young people from Berlin on daytrips to Wannsee. Weekly newsreels regularly report on leisure activities at the beach, bathing, and the latest swimwear.

The mountains are also a fashionable, more expensive holiday destination, which is reflected in the popular genre of the mountain film. Experienced mountain climbers and skiers film elaborate action scenes under extreme conditions. The director Arnold Fanck realizes feature and educational films and makes Luis Trenker and Leni Riefenstahl screen stars.

Individual and Type

Self-portrait of an anonymous young woman

Photo booth photo, 1930

Source: Günter Karl Bose, Berlin

In the early twentieth century, the preoccupation with the human face experiences an unforeseen upswing with the ostensibly objective medium of photography. The audience is fascinated by original physiognomies, such as those captured by the photographer Hans G. Casparius both on the film set and in his studio.

The tendency towards typification is also found in the medium of film. Particular stereotypes of physiognomy, clothing, and attitude are thus developed for “the proletarian child,” “the artist,” and “the industrialist.”

The appearance and poses of stars are frequently imitated by the cinema audience. This is particularly evident in so-called “photo-booth” images. The passport-sized photos are shot in automated photography machines and are often used for self-staging.

Cinema Architecture

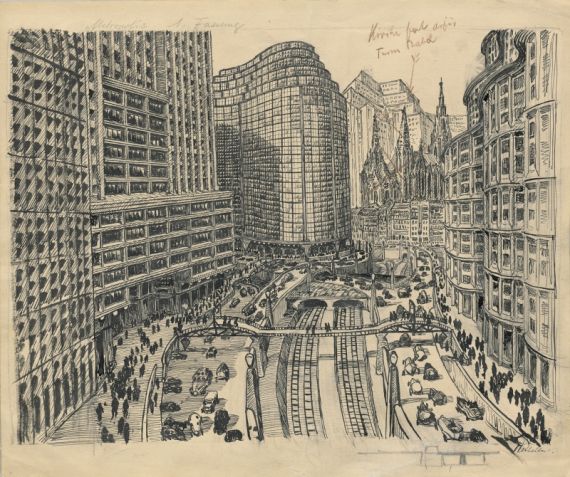

Sketch for a set design, “Metropolis, City, 1st Version” by Erich Kettelhut, 1927

Metropolis (1927, Fritz Lang)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Erich Kettelhut Archive

The “kintopp” of the 1910s develops into the fashionable “cinema palace” of the metropolis. With 2,000 seats in 1928, the Lichtburg cinema in Essen boasts one of the largest auditoriums in Germany.

The New Objectivity cinema designs by architects such as Erich Mendelsohn and Hans Poelzig are incunabula of modern urban architecture. With their rounded façades and interior walls, the Berlin cinemas Universum and Capitol am Zoo pick up on the dynamics of street traffic.

Their colorfully illuminated entrance façades celebrate the dazzling lifestyle of the 1920s. The commercial graphics of the time also follow the new artistic trends, from Expressionism to New Objectivity.

Mobility

Collage, presumably by Umbo

Berlin. Die Sinfonie der Grosstadt (Berlin. Symphony of a Great City, Walther Ruttmann, 1927)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive

As the pulsating capital of the republic, Berlin is a model for mobility and speed. Filmmakers capture this either directly on location, as in Berlin. Die Sinfonie der Großstadt (Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, 1927), or recreate elaborate streets and junctions in studios, as in Asphalt (1929). Storyboard-like series of drawings mark the changes in camera settings.

Thanks to easier-to-use gearshifts, driving also becomes more attractive to women. By 1929, 4.2 percent of women in Berlin already have a driver’s license. In Achtung! Liebe! Lebensgefahr! (Attention! Love! Mortal Danger!, 1929), the everyday life of a female racing driver is dramatically staged. The telephone is also a medium of acceleration in film. In particular, the comedy and the crime film take advantage of the possibilities of this new means of communication.

Exoticism

Kimono of Lola Lola (Marlene Dietrich)

Design: Tihamér Varady (Theaterkunst)

Der blaue Engel (The Blue Angel, Josef von Sternberg, 1930)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Marlene Dietrich Collection Berlin, Photo: Marian Stefanowski

In the early 1920s, Joe May shoots exotic adventure films in elaborate studio settings. Props for this are provided by, among others, ethnological museums. In contrast, Franz Osten realizes several feature films on original locations and with local actors in India. At the same time, cultural and expedition films are being produced all over the world, bringing previously unknown images from foreign countries to Germany. For the first time, the colonial point of view is questioned, as exemplified by the film Menschen im Busch (People in the Bush, 1930) by Friedrich Dalsheim and Gulla Pfeffer.

Among the few actors of Color in the cinema of the Weimar Republic are the Chinese American Hollywood actress Anna May Wong and the Afro-German actor Louis Brody. The films in which they act are characterized by an uncritical enthusiasm for the exotic, which is also reflected in the Chinese-style accessories and a special penchant for the kimono.

Interiors

Set design of a fitness room by Franz Schroedter

Die große Pause (1927, Carl Froelich)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Franz Schroedter Archive

New living and design concepts, inspired by the Bauhaus and New Objectivity, are immediately taken up in the form of film requisites. The ‘“new way of living” is also propagated in documentary films. In reality, Marcel Breuer’s tubular steel furniture can be found less in the middle-class flat than in the homes of artists and filmmakers in tune with modernism.

Film architects also use the interior to suggest a particular contemporary attitude. In Die große Pause (The Long Intermission, 1927), for example, the cubist glass doors and the wall painting reminiscent of the works of Oskar Schlemmer in an Art Nouveau villa are evidence of the open-minded worldview of its female inhabitant.

The Weimar Touch

Poster design by Josef Fenneker

King of Jazz (USA 1930, John Murray Anderson)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Josef Fenneker Collection

© City of Bocholt (Stadtmuseum Bocholt / Josef Fenneker)

Cinema in the Weimar Republic, its filmic innovations, aesthetics, themes, and not least of all its style of narration and dramatization still have a profound impact on the language of film to this day. What aspects of the cinema of that time continue to inspire contemporary filmmakers?

Current television series such as Babylon Berlin (since 2017) take us back to the days of the Weimar Republic and resurrect the myth surrounding it. They depict the people of the time–their longings and concerns–as though they were our contemporaries.

New Vision

Set photo Geheimnisse einer Seele (Secrets of a Soul, 1926, G. W. Pabst)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive

The establishment of cinematography marks a significant medial transition. Walter Benjamin recognizes that film had burst our perception of the world asunder with the “dynamite of the tenth of a second” and had substantially changed it. This enormous potential of cinematic art is discovered and explored in particular by avant-garde artists. For women with visual and narrative intuition, film provides new fields of professional activity.

Film critics contribute to the fact that, in the spirit of their writings, approaches to film theory are established which focus on stylistic and socio-political aspects of the seventh art. The diversity of the perspectives of both cinematic imagination and critical reflection testifies to the curiosity and joy of experimentation in the Weimar Republic.

“Was at the Movies. Wept.”

Scene from Die Liebe der Jeanne Ney (The Love of Jeanne Ney, 1937 G.W. Pabst)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive

Franz Kafka’s laconic diary entry from 1921–“Was at the movies. Wept.”–conveys the full spectrum of cinema impressions of longing, intimacy, and the escape from everyday life, which draws viewers in droves into the dark halls.

Among audiences of the 1920s, white-collar employees are strongly represented. In their diaries, they make notes, occasionally in shorthand, on which film they enjoyed most.

In addition to such anonymous testimonies, there are also diary entries made by prominent personalities such as the young Marlene Dietrich or the author Thea von Sternheim, who record their visits to the cinema with the same intensity.

Theory and Criticism

Scene from M (1931, Regie: Fritz Lang)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive

Siegfried Kracauer, Béla Balázs, and Walter Benjamin consider both the film itself and its impact. They investigate the longings of the audience for an attempt to escape from everyday life, criticize the pure aestheticism of filmmakers, and question the ideological motives of major film productions. Several women critics, including Lotte Eisner and Lucy von Jacobi, contribute to the diversity of opinion.

Over the years, a lively film criticism scene thus emerges, from which film theory gradually begins to develop. Most of the authors are driven out of Germany during the Nazi period; many of their notes are lost on their flight.

Thinking Film

Light-bulb

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo archive

The dream of the cinema is first spun in the form of a possibility. It is a question of exploring what film is and can be.

Walter Benjamin’s film library, the basis for his essay written in 1935 while in exile in Paris, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” is partially reconstructed here.

To this day, the works have lost none of their relevance. They have become classics of film theory.

Gallery

-

Set photo Film study (1928, dir: Hans Richter)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Fotoarchiv -

Asta Nielsen Dirnentragödie (Tragedy of the Street, 1927, dir: Bruno Rahn)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Fotoarchiv -

Women in the Eternal Garden, costumes designs by Aenne Willkomm

Metropolis (1927, dir: Fritz Lang)

Photo: Horst von Harbou

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive, © Deutsche Kinemathek – Horst von Harbou -

Set photo

Der Fürst von Pappenheim (The Masked Mannequin, 1927, dir: Richard Eichberg)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive -

Edith Posca as the detective Miss Madge Henway

Screenplay: Jane Bess

Das Achtgroschenmädel. Jagd auf Schurken. 2. Teil (1921, dir: Wolfgang Neff)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive -

Marlene Dietrich with her daughter Maria in Swinemünde, 1929

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Marlene Dietrich Collection Berlin -

Christl Ehlers, Wolfgang von Waltershausen, and Brigitte Borchert

Menschen am Sonntag (People on Sunday, dir: Robert Siodmak, Edgar G. Ulmer, Rochus Gliese, 1930)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Brigitte Borchert Archive -

Portrait of Rosa Porten, 1920s

Photo: Alexander Binder

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Photo Archive -

Poster design by Albin Grau, 1922

Nosferatu (1922, dir: F. W. Murnau)

Source: Kantonsbibliothek Appenzell Ausserrhoden / Trogen -

Poster design by Albin Grau, 1922

Nosferatu (1922, dir: F. W. Murnau)

Source: Kantonsbibliothek Appenzell Ausserrhoden / Trogen -

Sketch for a set design, “Metropolis, City, 1st Version” by Erich Kettelhut, 1927

Metropolis (1927, dir: Fritz Lang)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Erich Kettelhut Archiv -

Set design of a fitness room by Franz Schroedter

Die große Pause (1927, dir: Carl Froelich)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek – Franz Schroedter Archive

Credits

Artistic Director, Board: Rainer Rother

Executive Director, Board: Florian Bolenius

Artistic Director Bundeskunsthalle: Rein Wolfs

Executive Director Bundeskunsthalle: Patrick Schmeing

Curator: Kristina Jaspers

Media Curator: Nils Warnecke

Project Management Deutsche Kinemathek: Peter Mänz

Project Management Bundeskunsthalle: Susanne Annen, Angelika Francke

Curatorial assistance and scholarly research: Annika Haupts

Coordination: Vera Thomas

Scholarly Assistants: Anna Heizmann, Peter Riedl

Editor Deutsche Kinemathek: Karin Herbst-Meßlinger

Editor Bundeskunsthalle: Helga Willinghöfer

Translations: Gérard A. Goodrow

Design Exhibition Architecture and Graphics: Atelier Schubert, Stuttgart

Construction of Exhibition Architecture: Camillo Kuschel Ausstellungsdesign, Berlin

Conservational supervision: Sabina Fernández

Reproductions: d‘mage, Berlin

Engineering: Frank Köppke, Roberti Siefert

Media and Lighting Equipment: Stephan Werner

Media Editing: Stanislaw Milkowski

Graphic Design: Pentagram Design, Berlin

Head of Communications: Sandra Hollmann

Marketing: Linda Mann

Online Editor: Julia Schell

Press: Heidi Berit Zapke

Education: Jurek Sehrt

Guided Tours and Workshops: Jörg Becker, Kaaren Beckhof, Jürgen Dünnwald, Jessica Dürwald, Gitte Hellwig, André Meral, Thomas Zandegiacomo

Thanks

Our special thanks go to all colleagues of the Deutsche Kinemathek - Museum für Film und Fernsehen.

A joint exhibition of Deutsche Kinemathek, Berlin, and Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn.

Partners

The exhibition is supported by

Hauptstadtkulturfonds

In cooperation with

Bundeskunsthalle

Partners

Wall

Yorck Kinogruppe

alleskino.de

Media partners

arte

rbb Kultur

tip Berlin

The Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek is funded by

Die Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien