‘Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari’ (GER, 1920, directed by Robert Wiene)

© Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation

Be Caligari! – The Virtual Cabinet

13.2.20 – 9.8.21

General Information

Considered one of the most influential feature films in film history, ‘Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari’ (GER, 1920, directed by Robert Wiene) celebrated its premiere at Berlin’s Marmorhaus cinema on February 26, 1920. To mark its centennial, we are dedicating an exhibition to this Expressionist masterpiece.

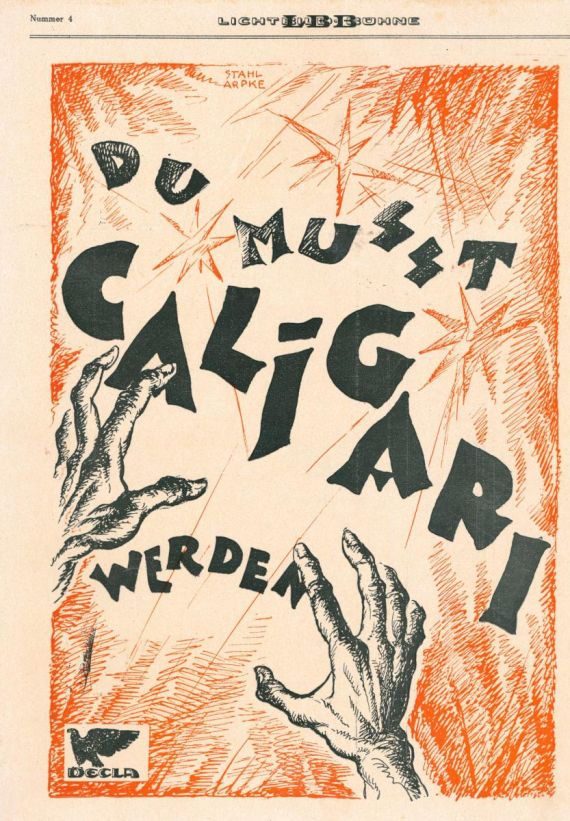

Building on the innovative advertising campaign (“Du musst Caligari werden!” / “Be Caligari!”) used at that time, the show traces the production history of this early psychological thriller. It also presents reconstructions of the movie’s spectacular sets based on historical models and drawings. Alongside the restored original version of the silent film, a Virtual Reality (VR) film ‘Der Traum des Cesare’ (‘Cesare’s Dream’) is a highlight of the exhibition. The volumetric film makes it possible for visitors to delve into the three-dimensional Caligari film space and to move virtually through the sets.

Key aspects

Virtual reality film Cesare’s dream

‘Der Traum des Cesare’ (2019)

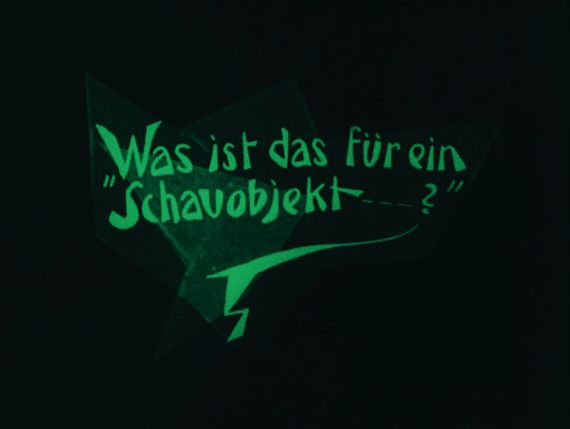

100 years after the premiere of ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’, a virtual reality production conceived by the Goethe Institut Warsaw and UFA X turns the story of the sleepwalker Cesare into an unusual experience. For ‘Cesare’s Dream’, a camera-based recording technology was used to create hologram images of real people. The combination of volumetrically recorded actors and a computer-generated environment allows the user to enter the set with the help of VR glasses and experience the silent film in a completely new way.

The users can now accompany Cesare and Dr. Caligari when they encounter each other between reality and dream. Virtual Reality (VR) is a new technology, with which viewers are invited to move freely in space and look around in all directions to change their perspective–because only in this way do various elements of the VR experience become visible.

Marketing

“For several weeks now, an admonishing hand on a number of posters has been urging: ‘Be Caligari!’ [...] Now we know why and are more than happy to stand behind the cinematic work,” wrote a critic of the ‘Berliner Abendblatt’ on February 28, 1920, referring to the marketing campaign launched by the production company Decla in the run-up to the film premiere: “Insiders asked: ‘Have you also already become Caligari?’ and one spoke of ‘Expressionism in film’” (‘Der Kinematograph’, March 3, 1920).

The illustration of the call to action with the two expressively contorted hands was designed by the graphic artists Erich Ludwig Stahl and Otto Arpke, who were also responsible for the German premiere poster of the film. A second motif, which was used for an advertising campaign, presents the lettering in a kind of “hypnotic vortex.” For the in-house program of the Marmorhaus cinema, its graphic artist Josef Fenneker designed an elaborate and colorful fold-out fan. The marketing campaign of 1920 helped to establish the myth of the film and, like the style of the film itself, still serves today as a point of reference.

The style

‘Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari’ (GER, 1920, directed by Robert Wiene)

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek

In 1920, ‘The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari’ was in tune with the zeitgeist and set standards. With distorted perspectives and grotesque costumes, a wave of so-called Expressionist films imitated the deliberately anti-realistic, fantastically stylized aesthetics of ‘Caligari’. In ‘Nosferatu’ (1922), F. W. Murnau once again picked up on the diffusely threatening atmosphere and thus established the genre of horror film. The open subplot in an insane asylum, which, in the end, (possibly) exposes the narrative as a delusion, established conventions of the psychological thriller. With hard contrasts and long shadows, film noir also picked up elements of the silent film classic, and Tim Burton paid tribute to ‘Caligari’ with the gothic style of many of his works. The character of Cesare was also a style-defining figure: With his black turtleneck, leggings, disheveled hair, and kajal eyeliner, Conrad Veidt created an iconic look as a sleepwalker, which is still often quoted by actors and rock stars to this day.

The legendary scenery

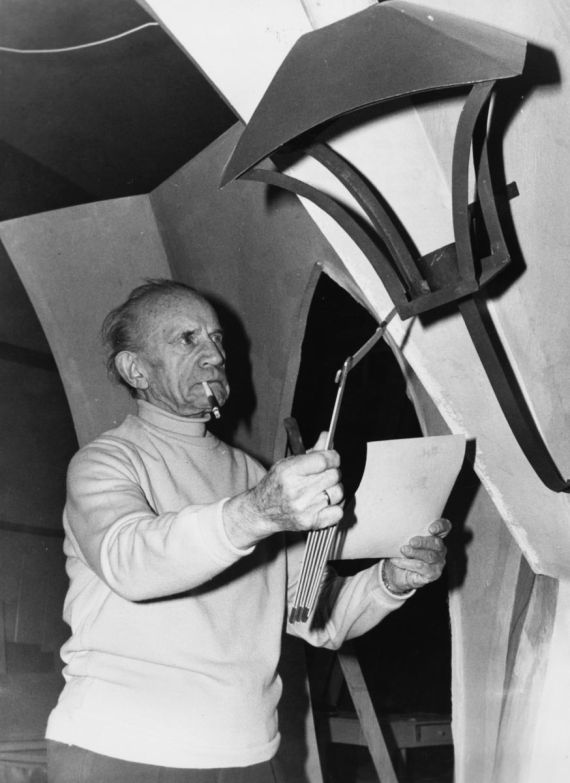

Große Internationale Filmkunst Ausstellung 1958, Munich

© Ingrid Hasenwinkel, source: Deutsche Kinemathek

Since the 1950s, there have been repeated attempts to reconstruct the legendary scenery in a museum context. In doing so, it was possible to draw on the expertise of the film architect Hermann Warm, who had designed the original sets together with Walter Reimann and Walter Röhrig. Together with his colleague Arno Richter, Warm reconstructed parts of the sets more or less in their original dimensions for the Munich exhibition “Internationale Filmkunst” (1958) and the Musée du Cinéma of the Cinémathèque française in Paris. In the mid-1960s, he made several models for the Deutsche Kinemathek, which were intended to illustrate the structure of the sets and their arrangement in the Lixie Studio in Weißensee, where the original filming took place. He also reconstructed his original set designs on the basis of the film version available at the time.

Fifty years after the world premiere, the Deutsche Kinemathek continued its examination of the silent film classic with the exhibition “Caligari and Caligarism” (1970) and interviewed contemporary eyewitnesses still alive at the time. Further exhibition presentations with newly discovered documents followed.

Efforts to restore the film

‘Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari’ (GER, 1920, directed by Robert Wiene)

© Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Foundation

The film itself has been restored several times. The improved technical possibilities and newly discovered source material led in several steps to the digital version of 2014, which is being screened here. The starting point for the restoration, which was carried out under the auspices of the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung under the direction of Anke Wilkening, is a well-preserved original camera negative from the Bundesfilmarchiv, which, however, lacked the first act. This was supplemented from other copies; the original intertitles from the archives of the Deutsche Kinemathek were inserted and the color toning restored. No further digital manipulation was undertaken; the mastering was done in 4K.

The original composition by Giuseppe Becce has been lost, although four pieces have been preserved in his “Kinothek”, a collection of piano pieces for film accompaniment. Young composers from the New Music Institute of the Freiburg University of Music under the direction of Cornelius Schwehr created the new soundtrack based on Becce’s accompaniment music. The music version was produced in cooperation with ZDF and ARTE.

Credits

Credits

Exhibition

Curators: Kristina Jaspers, Peter Mänz

Project Head: Peter Mänz

Project Management: Vera Thomas

Copy editing: Julia Schell

English translations: Gérard A. Goodrow

Graphic design (exhibition): Felder KölnBerlin

Exhibition architecture and installation: Camillo Kuschel, Adriaan Klein

Restoration (paper): Mirah von Wicht

Conservational supervision (paper): Sabina Fernández-Weiß

Set up of the VR installation: Fabian Mrongowius

Design of the advertising graphics: Pentagram Design

Design Gobo spots:Atelier Schubert

Media and editing: Nils Warnecke, Stanislaw Milkowski

Cesare’s Dream

Concept: Krzysztof Stanisławski

Coordination Goethe Institut: Renata Prokurat

Director (Capturing Director): Sebastian Mattukat

Creative Producer: Fabian Mrongowius

Art Director, Stage Setting, Designer: Nicolas de Leval Jezierski

Screenplay: Floris Asche

Design of the interior walls of the tent: Zdzisław Nitka

Sculpture of Cesare: Sylwester Ambroziak

Volumetric film: Volucap Studio UFA X Babelsberg

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Goethe Institut Warsaw, the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Stiftung and all colleagues at the Deutsche Kinemathek – Museum für Film und Fernsehen.

Partners

Supported by the

Die Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien

by a resolution of the German Bundestag

In cooperation with

Goethe Institut Warschau

Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau Stiftung

UFA X

Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin

-

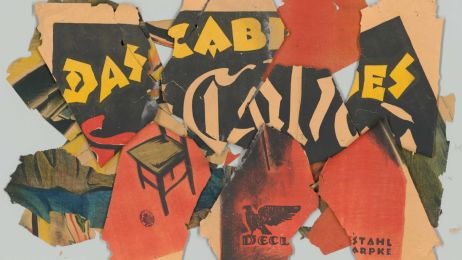

Burn Marks – Film Posters from a Salt Mine

To the ExhibitionFragments of a poster for the Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari were found in a salt mine in Grasleben, Germany. Learn more about the posters discovered in this salt mine in our special exhibition Burn Marks.