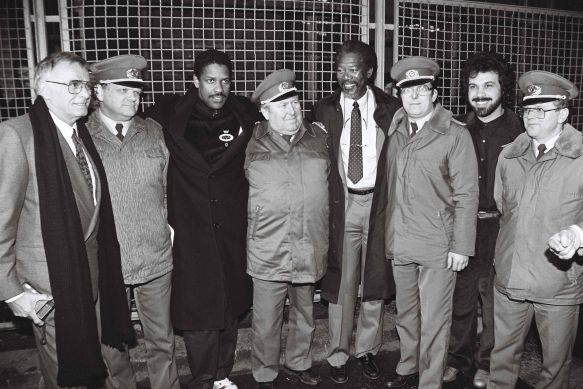

Edward Zwick, Denzel Washington, Morgan Freeman und Freddie Fields am Grenzübergang Invalidenstraße mit Grenzsoldaten, Berlin 1990

Foto: Mario Mach

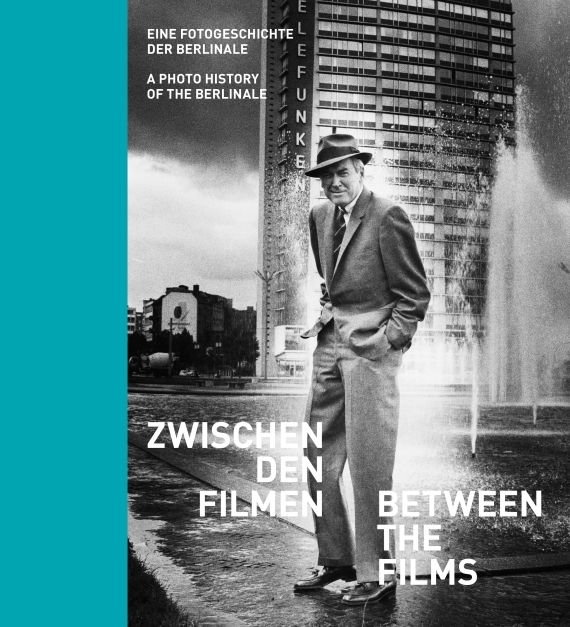

Between the Films – A Photo History of the Berlinale

28.9.18 – 5.5.19

Exhibition

-

Publication

Press photographers have accompanied and documented the Berlinale from the very beginning. This also had a lasting impact on the image of the Berlinale, which was founded in 1951 in what was then West Berlin as a true festival for the audience.

The heart of the exhibition, shown here for the first time, is photos made by Berlin press photographer Mario Mach (1923–2012), who accompanied the Berlinale professionally from the very beginning and until the 1990s. Like his colleagues Heinz Köster (1917–1967) and Joachim Diederichs (1924–2010), Mach was present at press events, from the appearance of the stars to their departure. Arrival at the hotel, the film premieres, walks around the city and the crowds of fans, the film ball, and awarding of the prizes were part of the established program.

The film-related material left by Mario Mach, as well as the collections of Köster and Diederichs, are stored in the photo archive of the Deutsche Kinemathek. Also found there are large portions of the work of Erika Rabau (?–2016), the official Berlinale photographer, who began this in the 1970s, as well as pictures taken by Japanese photographer and filmmaker Fumiko Matsuyama (1954–2014), who lived in Berlin and who was present at the Berlinale since the 1990s.

Complemented by the works of present-day Berlinale photographers like Gerhard Kassner and Christian Schulz, an extensive collection has been created. It not only depicts the history of the Berlinale, but also the day-to-day and cultural history of the Federal Republic of Germany, both before and after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The exhibition draws from this collection.

Trailer

Concept and Editor: Anna Bitter

Photos: Heinz Köster, Erika Rabau, Mario Mach

Source: Deutsche Kinemathek - Fotoarchiv

Key Aspects

Stars

They are the main attraction of every film festival – the actors and actresses who breathe life into the stories they tell on the screen and are loved by their fans for this. Stars like Isabelle Huppert or George Clooney are practically omnipresent at the Berlinale, because so many of their films have been premiered here. Other legends are suddenly there again after many years – as homage guests – like Jane Russell, Alain Delon or Shirley MacLaine.

Who is considered a star or just a starlet is decided less by the quality of their films, more by PR strategies, self-promotion and interest by the media. Press photographers play an important role in this.

Photographer Gerhard Kassner has been taking pictures of guests on behalf of the Berlinale at the Competition and Panorama since 2003. He has one and a half minutes to do so, after which his portraits are presented in the Berlinale Palast and signed by the stars there. Not every amateur actor or novice has the material it takes to become a star, but their photographer makes it look as though they do.

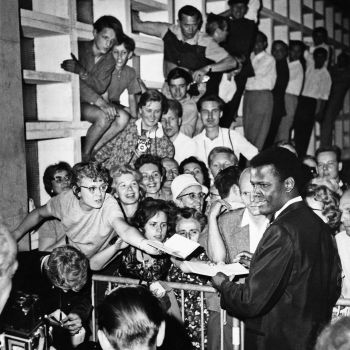

Fans

The great success the Berlinale has enjoyed with the public since it was founded was fundamentally linked, at least in the first two decades of the Festival, with the special position of West Berlin, which was increasingly isolated – especially after the Wall was built in 1961. The Festival, a summer event until 1977, reliably brought international glamour to the city. The Berlin public flocked in huge numbers to the events, some of which took place outdoors. Both German and international film stars were welcomed enthusiastically.

The first of the fans were already waiting at Tempelhof Airport to collect autographs. They also clustered in front of the Hotel Kempinski on the Kurfürstendamm, where an overly enthusiastic page often waited at the reception desk, not only to help a prominent guest with a suitcase, but also to ask for an autograph. In the 1950s, the Berlinale was a festival for the ordinary people.

The venues of the Berlinale may have changed in the meanwhile, but not the enthusiasm of the people of Berlin. Without their – sometimes a little intrusive – star cult, the Festival would attract less attention.

Politics

From the beginning, the Berlinale was also a political event. During the Cold War, it demonstrated the cultural diversity and internationality of the isolated West Berlin. Governing Mayors like Willy Brandt and Klaus Schütz insisted on opening the Festival and inviting honorary guests to West Berlin’s Rathaus Schöneberg. Star guests were occasionally received by German Presidents Walter Scheel and Richard Weizsäcker at Schloss Bellevue. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, German reunification became a theme for filmmakers from the old and new federal states, and their films were shown in all of the sections of the Berlinale.

The Berlinale was repeatedly a forum for political protest actions. In 1979, for example, the Soviet delegation withdrew its entries from the competition to protest the participation of the American Vietnam War drama THE DEER HUNTER, and a number of other socialist states followed it. Or in 2011, when director Jafar Panahi, who had been named to the Festival jury, was not permitted to leave his home country of Iran.

Today the guests of the Festival sign the Golden Book of the City of Berlin at the Rotes Rathaus, and politicians continue to enjoy being seen with the stars.

Parties

Dinners, receptions, balls, whether thematic or with live music, are an integral part of the Berlinale environment. Not only film producers or distributors call attention to themselves with parties, but also national representations, embassies, other festivals and institutions. Parties are especially intended as industry get-togethers, for strengthening contacts that already exist or creating new ones. The number of party invitations can be used to calculate the celebrity of a particular guest, or how highly he or she is esteemed within the industry.

Food – up to the Culinary Cinema of Festival director Kosslick – has always been important: While the European Festival audience of the 1950s was still enjoying the delicacies they had had to do without even in the post-war period, platters with open sandwiches and chicken legs were no longer enough a couple of decades later. Now the guests were also interested in the way the food was presented, and this had to be as unusual as possible. It is only since the 2010s that finger food is standard. This is appropriate, on the one hand, on the other not at all, in view of the necessity of frequently shaking hands.

Fashion

Although Berlin may be considered less than elegant in comparison with other international cities, it undergoes an amazing transformation during the Berlinale at any rate. Suddenly fashionable outfits can be seen during the day. In the evening, even in the cold February weather, women stride over the red carpet in strapless gowns and high-heeled sandals. Men in tuxedos play their part. The fact that there is no need to wear classic evening attire to be well dressed is demonstrated by the many individual styles of the guests who have come from all over the world – whether ethno, cross-dressing or streetwear.

During the first two decades of the Berlinale, the dress code was stricter and thus more uniform. Just the same, even then there were opportunities to differentiate oneself – such as with an unusual fabric or a hairpiece.

The photos in this area also show that fashion is cyclical, such as when a satin dress for the evening resurfaces again 20 years later with slight variations. On the other hand, there is an inexhaustible supply of textiles, from which anything can be combined with anything else.

Couples

Conferences, meetings, sightings, receptions: The professional visitors to the Berlinale generally have an appointment schedule that is filled to the brim. After all, the Berlinale is a giant meeting place for the industry, one whose most important function is networking.

But the Festival is also a place for planned and unplanned encounters, for relaxing with friends you meet, for random conversations between a star and a fan, producer and director, agent and actor, between regular guests of the Festival and newcomers – and erotic attraction doesn’t hurt here either.

Photos taken here show situations like two actors meeting again for the first time after they have made a film together, a press conference conducted jointly by two totally antithetical directors, the father-daughter relationship between a director and his lead actress, or the unexpectedly fond encounter of two legendary actors.

Meetings and pairings also take place in the non-professional sphere: waiting together in line to buy tickets or to go into the movie theater, at the late screenings of a special series, or a quick coffee between the films. The photographers are only interested in these on occasion.

Cinemas

The first venues of the Berlinale, which took place during the summer until 1977, were the Titania-Palast in Steglitz, the Waldbühne and the Summer Garden at the Berlin Radio Tower.

Already added in the second year were the Delphi on Kantstrasse and the Capitol on the upper part of the Kurfürstendamm as Festival cinemas. Some films were also shown afterwards at the so-called Randkinos (marginal cinemas), the Corso in Wedding and the Metro-Palast in Neukölln. Until the Wall was erected in 1961, a certain number of tickets were reserved for visitors from the Soviet sector.

In 1957, the newly built Zoo Palast became the main venue for the competition. In 1958, the Festival was opened in the Kongresshalle in the Tiergarten, which had just been erected. There Willy Brandt, as the new governing mayor, greeted guests from all over the world. For a certain period of time, the Press Center of the Berlinale was located here. Now the Kongresshalle is the center of the Haus der Kulturen der Welt.

In 2000, the Berlinale was relocated from the western part of the city to the recently completed Potsdamer Platz, once the intersection of East and West. Since 2010, under the motto “Berlinale Goes Kiez,” part of the program is also shown in less central districts.

Bears

At the beginning, it was bronze plates that were presented to the winners at the Berlinale. At that time, the audience was permitted to decide on their favorite films. Since the Festival received so-called “A” status in 1956, an international jury made up of film critics and filmmakers has decided which films would be recognized. Since then, a Golden Bear statuette has been the prize for the best films in the competition. Winners in the secondary categories are awarded the Silver Bear. The statuette of a standing bear, about 20 cm high, was designed by Berlin sculptor Reneé Sintenis in line with a design dating from 1932. The replicated animal greeted with his right arm at first, from 1961 on with his left arm.

Anyone who is given a bear has often traveled from far away, has spent strenuous days at the Festival, and is sometimes more surprised, sometimes less. Almost everyone who receives this award clearly shows how pleased he is, even if the way this is expressed may vary a little. Part of the ritual is that of profuse admiration for and showy presentation of the Bear, which is – as the long number of individuals that have been so honored remember – collect at the end of the stage and is a series product.

Press

From the very beginning, the Berlinale was documented by assiduous photographic reporters. Upon arrival at Tempelhof Airport, the guests were already welcomed not only by official representatives of the Festival, but also by photographers and reporters. The first phrases of interviews were already recorded before the actual events of the Berlinale had begun. And the cameras of the press were already clicking away incessantly – during the boat excursion on the Havel as well as at the wine tasting at Hotel Gehrhus in Grunewald. Welcome motifs were also offered by the annual Film Ball and the departure of the guests.

Archived at the Deutsche Kinemathek is the work of several photographers who concentrated on events relevant to film. Mario Mach and Heinz Köster were affiliated with the Festival from the very beginning. Since the early 1970s – and until the 2000s – Erika Rabau was the official Berlinale photographer. At present, it is photographers like Gerhard Kassner and Christian Schulz who define the image of the Berlinale.

Their photos depict various aspects of a long story dealing with the city and culture, the stars and their audience, rituals and representation, want and abundance, private and public spheres, and changes in values.

City

When the Festival posters start to appear all over the city in the middle of January, Berlinale fever begins. From the outset, the Berlinale has put a visual stamp on the urban landscape, and the city has profited from the Festival as much as conversely.

Stars are regularly invited to take tours of the city – with pride in the reconstruction and architectural postwar modern architecture that increasingly marked West Berlin, the new Hotel Kempinski on the Kurfürstendamm as well as the Hansaviertel. As of 1962, a look at the now completed Wall was considered obligatory for international guests. In the 1990s, after it fell, they admired the Brandenburg Gate as a symbol of the reintegration of the city, and the Berlinale soon moved from the West to Potsdamer Platz.

This is where the Festival guests have been concentrated since 2000: filmmakers, industry leaders, journalists and photographers from all over the world, the Berlin public, but also still the fans waiting for their stars in front of the hotels. A state of emergency prevails on Potsdamer Platz in February.

Gallery

-

Zoo Palast, 1957

Photo: Heinz Köster, © Deutsche Kinemathek -

James Stewart in front of the Telefunken highrise on Ernst-Reuter-Platz, Berlin, 1962

Photo: Heinz Köster, © Deutsche Kinemathek -

2010, Actress Mitra Hajjar

Photo: Alexander Janetzko, © Alexander Janetzko / Berlinale -

Advertising coup – film festival bobble caps for sale at the first winter Berlinale; 1978

festival director Wolf Donner (not wearing a cap)

Photo: Mario Mach, © Deutsche Kinemathek -

Berlinale Photographer Erika Rabau, 1995

Photo: © Marian Stefanowski -

Actor Sidney Poitier at the Kongresshalle, 1964

Photo: Heinz Köster, © Deutsche Kinemathek -

Nick Cave, 2006

Photo: Gerhard Kassner, © Gerhard Kassner / Berlinale -

Judi Dench and Berlinale-Director Dieter Kosslick, 2007

Photo: Ali Ghandtschi, © Ali Ghandtschi / Berlinale

Credits

Artistic director: Rainer Rother

Administrative director: Florian Bolenius

Curator: Daniela Sannwald

Project management: Peter Mänz

Exhibition coordination: Georg Simbeni

Photo archive: Julia Riedel

Audio comments: Hans Helmut Prinzler

Lectorship: Rolf Aurich

Translations: Native Speaker, Berlin

Design of the exhibition architecture and exhibition graphics: Franke | Steinert, Berlin

Exhibition construction and presentation: Camillo Kuschel

Passepartouts: Sabina Fernández-Weiß

Reproductions: d‘mage, Berlin

Framing: Anna Heizmann, Peter Riedl, Tarek Strauch

Technical services: Frank Köppke, Roberti Siefert

Light and audio installations: Stephan Werner

Design of the advertising graphics: Pentagram Design, Berlin

Marketing: Linda Mann

Press office: Heidi Berit Zapke

Trailer: Anna Bitter

Educational services: Jurek Sehrt

Guided tours: Jörg Becker, Thomas Zandegiacomo, Jürgen Dünnwald, SISKA

Special thanks

Despite all our best efforts, we haven’t been able to identify the copyright owners

of every image. In case of unacknowledged rights, please feel free to contact the

Deutsche Kinemathek – Museum für Film und Fernsehen.

Special thanks to:

We would like to express our special gratitude to all the photographers who supported

us with their work. A warm thanks is also due to Wolfgang Jacobsen, historian of the

Berlinale, as well as all Deutsche Kinemathek colleagues involved in this exhibition.

and:

Raphael Walser, Franke | Steinert

André Grzeszyk, Anne Marburger, Berlinale

Gabriele Bohm, Wiltrud Hembus, rbb

Frank-Manuel Peter

Partners

The exhibition is supported with funding from the:

Hauptstadtkulturfonds

In Cooperation with:

International Filmfestival Berlin

EMOP – European Month of Photography Berlin

Media Partner:

radio eins rbb

tip Berlin

The Deutsche Kinemathek is supported with funding from the

Die Beauftragte der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien